The figures you find in #1 raise some obvious

questions:

- What is the meaning of Christian identity in Western Europe

today?

- And how different are non-practicing Christians from religiously

unaffiliated Europeans – many of whom also come from Christian

backgrounds?

The Pew Research Center study – which

involved more than 24,000 telephone interviews with randomly selected

adults, including nearly 12,000 non-practicing Christians – finds that

Christian identity remains a meaningful marker in Western Europe, even

among those who seldom go to church. It is not just a “nominal”

identity devoid of practical importance. On the contrary, the

religious, political and cultural views of non-practicing Christians

often differ from those of church-attending Christians and religiously unaffiliated adults. For example:

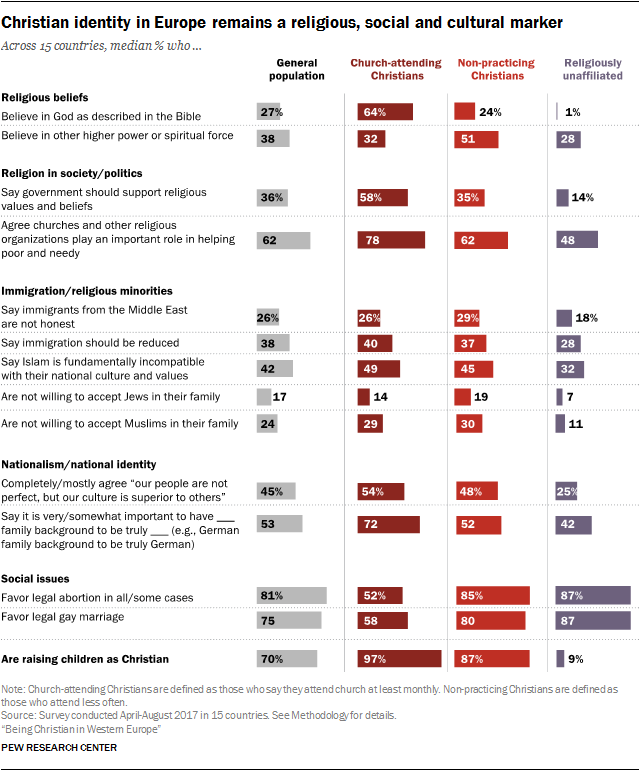

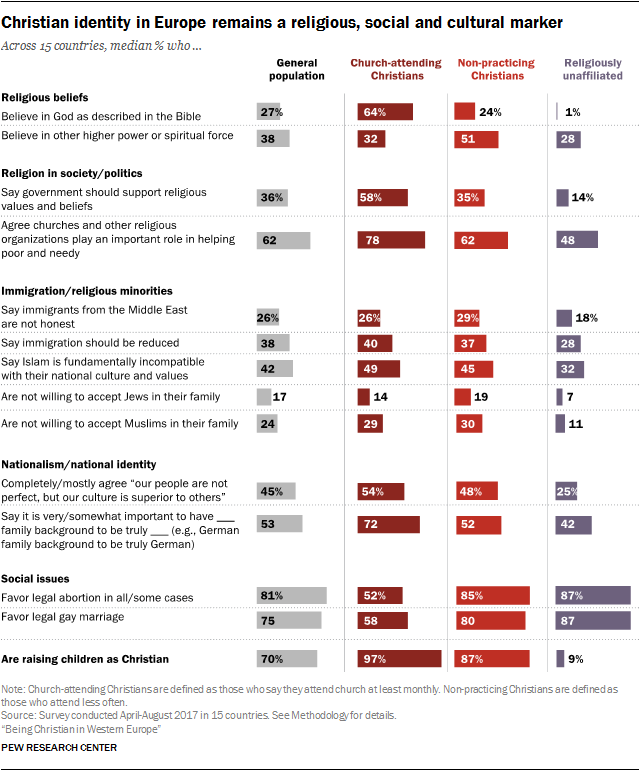

- Although many non-practicing Christians say they do not believe in

God “as described in the Bible,” they do tend to believe in some other

higher power or spiritual force. By contrast, most church-attending

Christians say they believe in the biblical depiction of God, though of most of them we do know they believe in the human doctrinal god, namely the trinity. And a

clear majority of religiously unaffiliated adults do not believe in any

type of higher power or spiritual force in the universe.

- Non-practicing Christians tend to express more positive than

negative views toward churches and religious organizations, saying they

serve society by helping the poor and bringing communities together.

Their attitudes toward religious institutions are not quite as favourable

as those of church-attending Christians, but they are more likely than

religiously unaffiliated Europeans to say churches and other religious

organizations contribute positively to society.

- Christian identity in Western Europe is associated with higher

levels of negative sentiment toward immigrants and religious minorities.

On balance, self-identified Christians – whether they attend church or

not – are more likely than religiously unaffiliated people to express

negative views of immigrants, as well as of Muslims and Jews.

- Non-practicing Christians are less likely than church-attending

Christians to express nationalist views. Still, they are more likely

than “nones” to say that their culture is superior to others and that it

is necessary to have the country’s ancestry to share the national

identity (e.g., one must have Spanish family background to be truly

Spanish).

- The vast majority of non-practicing Christians, like the vast

majority of the unaffiliated in Western Europe, favour legal abortion and

same-sex marriage. Church-attending Christians are more conservative on

these issues, though even among churchgoing Christians, there is

substantial support – and in several countries, majority support – for

legal abortion and same-sex marriage.

- Nearly all churchgoing Christians who are parents or guardians of

minor children (those under 18) say they are raising those children in

the Christian faith. Among non-practicing Christians, somewhat fewer –

though still the overwhelming majority – say they are bringing up their

children as Christians. By contrast, religiously unaffiliated parents

generally are raising their children with no religion.

Religious identity and practice are not

the only factors behind Europeans’ beliefs and opinions on these issues.

For instance, highly educated Europeans are generally more accepting of

immigrants and religious minorities, and religiously unaffiliated

adults tend to have more years of schooling than non-practicing

Christians. But even after statistical techniques are used to control

for differences in education, age, gender and political ideology, the

survey shows that churchgoing Christians, non-practicing Christians and

unaffiliated Europeans express different religious, cultural and social

attitudes. (

See below in this overview and

Chapter 1.)

These are among the key findings of a new

Pew Research Center survey of 24,599 randomly selected adults across 15

countries in Western Europe. Interviews were conducted on mobile and

landline telephones from April to August, 2017, in 12 languages. The

survey examines not just traditional Christian religious beliefs and behaviours, opinions about the role of religious institutions in society,

and views on national identity, immigrants and religious minorities,

but also Europeans’ attitudes toward Eastern and New Age spiritual ideas

and practices. And the second half of this Overview more closely

examines the beliefs and other characteristics of the religiously

unaffiliated population in the region.

While the vast majority of Western

Europeans identify as either Christian or religiously unaffiliated, the

survey also includes interviews with people of other (non-Christian)

religions as well as with some who decline to answer questions about

their religious identity. But, in most countries, the survey’s sample

sizes do not allow for a detailed analysis of the attitudes of people in

this group. Furthermore, this category is composed largely of Muslim

respondents, and general population surveys may underrepresent Muslims

and other small religious groups in Europe because these minority

populations often are distributed differently throughout the country

than is the general population; additionally, some members of these

groups (especially recent immigrants) do not speak the national language

well enough to participate in a survey. As a result, this report does

not attempt to characterize the views of religious minorities such as

Muslims, Jews, Buddhists or Hindus in Western Europe.