Non-practicing Christians widely believe in God or another higher power

Of those who call themselves Christian the majority believe in the Trinity and not as such as Pew count them as believers in God as described in the Bible. In the 27% who believe in God, the majority believe in a concept they were brought up with, some Catholics even not knowing that their church worships a Trinity, or do not know what it entails. Non-trinitarian Christians though still may be counted as the minority

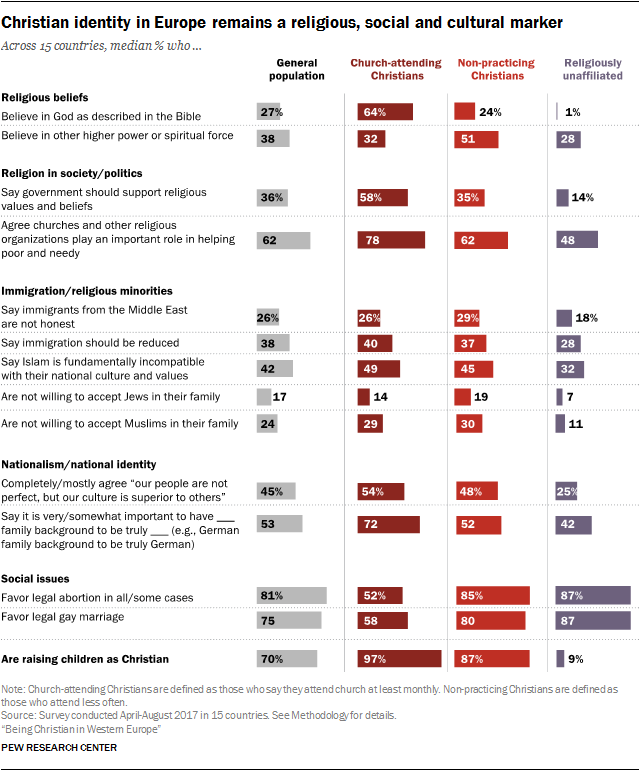

Most non-practicing Christians in Europe believe in God. But their concept of God differs considerably from the way that churchgoing Christians tend to conceive of God. While most church-attending Christians say they believe in God “as described in the Bible,” non-practicing Christians are more apt to say that they do not believe in the biblical depiction of God, but that they believe in some other higher power or spiritual force in the universe.

For instance, in Catholic-majority Spain,

only about one-in-five non-practicing Christians (21%) believe in God

“as described in the Bible,” while six-in-ten say they believe in some

other higher power or spiritual force.

Non-practicing Christians and “nones” also

diverge sharply on this question; most unaffiliated people in Western

Europe do not believe in God or a higher power or spiritual force of any

kind. (See below for more details on belief in God among religiously unaffiliated adults.)

Similar patterns – in which Christians

tend to hold spiritual beliefs while “nones” do not – prevail on a

variety of other beliefs, such as the possibility of life after death

and the notion that humans have souls apart from their physical bodies.

Majorities of non-practicing Christians and church-attending Christians

believe in these ideas. Most religiously unaffiliated adults, on the

other hand, reject belief in an afterlife, and many do not believe they

have a soul.

Indeed, many religiously unaffiliated

adults eschew spirituality and religion entirely. Majorities agree with

the statements, “There are no spiritual forces in the universe, only the

laws of nature” and “Science makes religion unnecessary in my life.”

These positions are held by smaller shares of church-attending

Christians and non-practicing Christians, though in most countries

roughly a quarter or more of non-practicing Christians say science makes

religion unnecessary to them. (For a detailed statistical analysis

combining multiple questions into scales of religious commitment and

spirituality, see Chapters 3 and 5.)